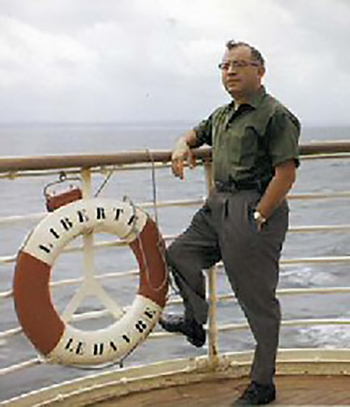

Dr. Franz Schachter

In the late 1930s, my father was at the beginning of a prestigious career as a professor of pathology at the University of Vienna Medical School. When Hitler swept through Eastern Europe, Dad fled Austria to the safety of France. He hired a beautiful blond student from the Sorbonne to tutor him in French and began working as a physician in Paris.

His security was destroyed again when German troops took over his newly adopted city. He tried to keep a low profile but was soon rounded up and taken to a detention center on the outskirts of Paris. He was slated to be deported to the work camps in Germany when he treated and cured a guard of a painful skin problem. In gratitude, the guard helped my father to escape. He gave my Dad a clean overcoat and a German hunting hat with a jaunty feather and Dad walked out of the prison camp in the middle of the day. Along with his tutor, who became my mother, he traveled across Europe in an effort to evade capture and reach America. He finally landed in Portugal and in a series of events straight out of the movie, “Casablanca,” my parents secured passage to Cuba and then to the United States.

They landed in New York and Dad set up a general practice in the South Bronx. Our first home was a ground-floor three-room apartment. We lived in the back bedroom and his office was the front dining room and living room. Dad loved his patients and they returned the feeling. The South Bronx was and still is a very poor neighborhood and in the days before Medicare and Medicaid, his patients often had no money to pay for health care. When they could not even afford the two dollars he charged for a visit, Dad never billed them, pressing in their hands’ sample packets of free medication as they left. To show their gratitude, they gave him what they could and our house was always filled with homemade coffee cake, mufflers, preserves and for some reason, a seemingly inexhaustible supply of hand-painted ties.

Dad made house calls every night and when I grew old enough, he would take me along At first I would just sit in the car, waiting for him to come back and tell me about the people he had just seen. When I entered my teens, he would take me in to see the patients. One night we went to see a woman with poorly controlled diabetes. She was in pulmonary edema and gasping for breath. To me, she looked hours away from death. My Dad calmly reached into his black bag for a shot of Mercuhydrin, a diuretic, and a tablet of digitalis. The next evening when we returned, the “dying woman” was sitting up in bed knitting a bright green muffler for her doctor. That was the night I decided to become a doctor, just like my Dad.

Dad died just as I was beginning my internship at Bellevue. I still miss him and so do his patients. Several times a year when people see my name on a charge slip or name tag they will say, “Schachter? Are you by any chance related to Dr. Schachter from Avenue St. John in the Bronx? ” When they hear he was my father, they tell me another story of his compassion and care that he gave them and their family. Franz Schachter taught me to be a better man as well as a better doctor and it is his approach to patient care that I have tried to pass along to my medical students and residents.